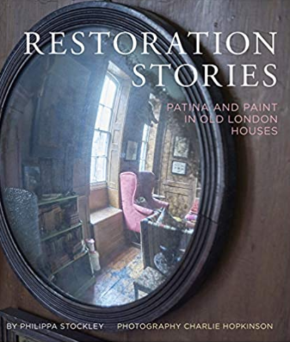

Restoration Stories: patina and paint in old London houses

Restoration Stories: patina and paint in old London houses, Phillipa Stockley, photography Charlie Hopkinson, 2019, 223 pages, Pimpernel Press, hardback.

As the novelist Ralph Ellison phrased it, old houses speak to our ‘lower frequencies’. They resonate with us in ways that can be hard to explain, talk to bits of us of which we were unconscious. Like moths to a pheromone trap, open the door to these houses and you are ensnared.

This book features 16 London houses, mainly 18th and early- 19th century in Spitalfields, where the owners have been happily ensnared. But just as the buildings nurture us, they also need us to nurture them. These are stories of thoughtful and considerate conservation. Stockley, an architectural and interiors journalist, calls the owners ‘modest, conscientious conservationists.’

Of one owner she writes: ‘He has done very little, and that when only absolutely necessary’. Another is allowing 10 years to scrape back the paint layers and yet another owner bemoans the need to put a bathroom in the house at all: ‘nothing ruins a Georgian house like too many bathrooms.’

It is no surprise that many of the houses are inhabited by artistic people: a sculptor, a paint maker, a jeweller, a film-maker and a writer, among others. Perhaps they are more driven by their emotional connection to the building and its aesthetics, and less likely to look at the uncomfortable facts. Many had highs of finding panelling or fireplaces behind plasterboard, or flagstones under concrete and lino. The flip side was finding unsupported beams with rotten ends, holes in the roof or dry rot.

One owner recalls that his basement had been a bomb shelter and was lined with concrete, the windows filled with concrete blocks; another that the boiler belched out carbon monoxide fumes and the cooker was called the Falcon Dominator. But dominating is not what these owners do. These are stories of quietly listening and encouraging the building to be itself; the antithesis of imposed industrial-strength facelifts.

Along with the hob grates, rim locks and hinges that were painstakingly sourced, many of the owners also had to acquire nerves of steel. One owner took on a Spitalfields house thinking there was not much to do, only to find that, actually, there was everything to do. Her husband left in the middle of the project and, with her finances depleted, she wondered how to continue. She recounts a visit from her structural engineer. ‘He said “Once in every 100 years a house needs a decent owner and, fortunately for this house, Oriel, that’s you.” And I thought, oh shit.’ But, reader, she completed the project and lives in the house still.

Many of these houses were saved by the Spitalfields Trust, which began when Dan Cruickshank squatted in a partially demolished house of 1725 to prevent further destruction. The trust has gone on to be hugely successful, having rescued over 70 buildings since 1976 with the motto: ‘Do not be afraid to go where others demur. Saving and finding a new use for an historic building is more important than profit.’

In the 1970s and 80s Cruickshank could be found quietly salvaging bits of panelling, ironmongery and fireplaces from skips, discarded by less sympathetic owners. He stored them safely until a building found a sensitive owner to whom the original fabric was returned. The house that he squatted in is once again a home, and it features in the book.

There is gorgeous photography recording how some owners live in spartan splendour with just a few sticks of furniture, while others furnish their houses as if they were a Blenheim or a Houghton. Chipped paintwork, nail-scarred timber, wobbly glass and worn furniture feature throughout, drawing the reader into the stories. One owner explains being drawn to ‘splits and repairs in panels, and I like teapots with mended handles, or porcelain bowls with staples.’

This atmospheric book shows the virtues of patient and thoughtful conservation. It is one to recommend to anyone who wants their listed building consent now and the project finished tomorrow. It might just open their eyes to a slower form of conservation and the benefits of a light hand.

This article originally appeared as ‘A light hand’ in IHBC's Context 164 (Page 51), published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in March 2020. It was written by Kate Judge, architectural historian.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?