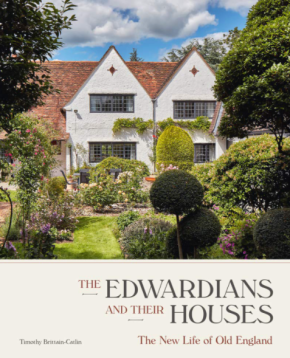

The Edwardians and Their Houses: the new life of old England

The Edwardians and Their Houses: the new life of old England, Timothy Brittain-Catlin, Lund Humphries, 2020, 224 pages, 126 colour and 74 black and white illustrations.

The popular image of the brief Edwardian period, extended slightly beyond Edward’s death to the outbreak of the first world war, is frequently expressed in terms of an Indian summer, a coda to the expansive achievements (whether now considered for good or ill) of Victoria’s later reign. With hindsight, imperial overstretch and relative industrial decline were already clearly apparent by the turn of the 20th century, revealed by a challenging war in South Africa, occasional jostling in the western hemisphere in relation to an equally expansive USA, and an escalating naval rivalry with imperial Germany. At home, the period started with a Conservative administration but soon turned to a period of Liberal government, albeit one sustained in office by Irish MPs and dependent on the perennial ebbs and flows of the ‘Irish question’.

However, there was still ample money about for some. Brittain-Catlin advances an intriguing argument that the fundamentally different routes by which any particular family obtained it, influenced not only their political stances but also their architectural influences adopted during the domestic building boom in Edwardian England. His theory, oversimplified for the purposes of review, is that ‘Liberal’ money from public administration, trade or commerce tended toward a continuation of support for the first wave of the arts-and-crafts movement, or a finer-grain advancement of the vernacular revival, while ‘Tory’ money from landed interests or banking was expressed in a new classical revival. These impulses stemmed from profoundly different expressions of national character and identity. ‘Liberal’ from the yeoman traditions of the 16th and 17th centuries were steeped in romantic visions of a comfortable pastoral life, the ‘Tory’ position was derived from and inspired by the imposing landed estates of the 18th century.

When one examines this notion against the architectural record, there may be something in it. Lutyens, for example, had built most of his exquisite arts-and-crafts villas by the death of Victoria. By 1904, he was tending towards the classical expression, which would eventually culminate in the imperial splendours of New Delhi and the post-war architectural identity of the Midland Bank. Was he leading fashion in this creative journey, or following a market demand from a specific echelon of society? (Successful as he was, it is well known that he regretted his ‘trade’ client’s architectural whim while designing Castle Drogo, around 1911, although evidently not enough to decline the commission). On the other hand, CFA Voysey would remain loyal to his very personal vision of the arts and crafts, realised predominantly in the nooks and crannies of the Home Counties or the Lake District, until commissions dried up with the outbreak of war.

Brittain-Catlin tends to avoid such heavily tilled ground and concentrates attention on a plethora of other architects operating in the period, a few like Clough Williams Ellis or Morley Horder just beginning their careers, others such as Caroe or Baillie Scott caught at the zenith of their powers, to some who have been somewhat forgotten unless we happen to run into their surviving buildings over the course of a site visit. With the occasional maverick exception, such as the brilliant Halsey Ricardo or the young Charles Holden, the talent that each architect plainly demonstrates, through the lens of many beautiful photographs, is a profound capacity to understand and assimilate the localised architectural expression and the craft skills of the 15th to the late 17th centuries, and the capacity to reproduce these anew, occasionally with such skill and conviction that their efforts can trick the unwary into believing them genuine to the present day.

In the light of the manifest inhumanities of earlier centuries, it is unsurprising that many turn their backs today on the countless injustices of history and regard nationalism in all its forms as anathema. Although superficially confident, Edwardian England too was a turbulent place founded on overwhelming inequalities at home and abroad. However, this book demonstrates that there were many talented people then who sought to find beauty as well as national pride in specific, if idealised, aspects of the past. Perhaps this impulse was a healthier and ultimately more progressive path than some of the blanket rejections of our shared history that many seem drawn towards today. If nothing else, it certainly left a rich legacy of beautiful and useful buildings.

This article originally appeared as ‘Money talks’ in Context 166, published by the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC) in November 2020. It was written by Michael Scammell, a conservation officer for the South Downs National Park Authority.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?