The Commons

• Animated Word Cloud depicting keyword metadata from the essays contained in this article

[edit] Essay 1: What are social goods? What is the commons?

This essay assumes that social goods are 'goods which are inclusive (non-excludable); free; universally accessible; not for sale; not for privatisation; belonging to the commons' (see Roth in Lesson 1).

[edit] • 1.1 What do we know?

In 1948, the National Health Service was set up by Aneurin Bevan MP, to be "a free and universally accessible system of health care, publicly owned and publicly funded through general taxation" (Unite). Since 2010, however, Jeremy Hunt MP has encouraged a number of private corporations to compete for and win contracts thus restricting access to the NHS on the basis of private ownership (p.4, 'Unite guide to Privatisation of the NHS').

In 1964, the Robbins Principle was introduced by Baron (Edward) Boyle of Handsworth, to make available "university places for all who were qualified" (Robbins Report). Since 1998, however, starting with the replacement of maintenance grants with tuition fees and student loans by David Blunkett MP and continued under successive Ministers, access to university places has become increasingly restricted on the basis of price to the point where outstanding debt on loans stood at £100.5bn in March 2017 (The Guardian, 15 June 2017).

Thus we know from these two examples that individuals and corporations can affect the commons either positively or negatively.

[edit] • 1.2 Why do we care?

The initiatives by Bevan and Boyle and the counter-initiatives by Hunt et al. and Blunket and his successors represent two different types of social worlds - those in which "you can have a common good and you can organize the society in accordance with that" (Moon, Lesson 2) and those in which "there is not much of a common good" (ib.).

In 'The Penguin and the Leviathan', Benkler characterizes the models of cooperation and self-interest and suggests that we care because we prefer one model and the values it embodies over the other.

It is also an established fact that the British have a strong emotional attachment to their NHS (New Statesman, January 2013).

Thus this essay argues that the cooperative (Penguin) model of the social world exemplified by Bevan and Boyle is preferable to the self-interest (Leviathan) model of the social world represented by Hunt etc.

[edit] • 1.3 What can we do?

In the final chapter of his book, Benkler suggests that we need to be aware of the role of cooperation in the design of successful systems.

Bevan and Boyle were from opposite ends of the political spectrum in the UK but each designed a relatively successful system - sixty-nine years and still going in the case of the NHS, and during 1964-1998 in the case of free university places. This indicates that the role of cooperation is better understood in relation to the NHS than it was to university places.

This essay concludes therefore, firstly, that the NHS most successfully meets the qualities of social goods set out in the premises above; secondly, that we can continuously redesign the NHS to be more successful; and, thirdly, that we can emulate the design of the NHS in the design of the educational system as a whole in order to change the world.

[edit] References

Fellows, N. (2017) 'What are social goods? What is the commons?', extremelyprovocative.com

https://www.coursera.org/learn/world-change/home/week/1

[edit] Essay 2: What are social goods? What is the commons? (2)

This essay assumes that public education is a commons in the East Midlands in England and that we can reconstruct it.

[edit] • 2.1 What do we know?

Firstly, we know that:

- a commons is a resource to which a community has free access [1a][1b];

- social goods can be defined, after Roth, as "inclusive (non-excludable); free; universally accessible; not for sale; not for privatization; and belonging to a commons" [2].

Secondly, then, we know that people use public education in the East Midlands in a complex variety of ways including, for example, their use of social goods belonging to it, namely:

- part-time voluntary pre-school education at nursery schools (ages 3-4)

- full-time compulsory education at primary schools (ages 4 or 5-11), secondary schools (ages 11-16), and special schools (ages 4 or 5-16)

- full-time post-compulsory education at schools and sixth form colleges (ages 16-18); and further education

[3].

Thirdly, we also know that public education in the East Midlands is being depleted as a result of funding cuts [4] and that free access to higher education is no longer available since it was abandoned in 1998 with the introduction of tuition fees [5].

[edit] • 2.2 Why do we care?

Moon has suggested that there are two different types of social worlds - those in which we can have a common good and those in which we can't [6]. People who care about public education do so because they recognize its value. Hence they prefer the former type and have therefore developed rules and norms to prevent its depletion. For example:

- the Education Act, 1944 [7] guaranteed free education to every child aged 5-14 and established norms regarding class sizes, pupil:staff ratios, curriculum content, etc.

- the Robbins Principle ruled that university places "should be available to all who were qualified for them by ability and attainment" [8].

The depletion of public education in the East Midlands, however, represents a preference for the latter type. Unfortunately, the regional campaigns by parent-led organizations [9] and by students [10] have failed to prevent the continuing depletion.

Thus this essay argues that public education in the East Midlands requires the most radical contribution.

[edit] • 2.3 What can we do?

Butler has warned that "legislation can do little more than pave the way for reform" [11]. What Butler did not anticipate, however, was that the Education Act, 1944 would be sabotaged by the Education Reform Act, 1988 [12], which effectively began the depletion of public education.

Therefore, the most radical contribution to public education in the East Midlands is to advocate universal access [13].

If this advocacy is accepted then its impact will be far-reaching. For example, universal access to public education in the East Midlands will mean that we can provide free access to the following social goods:

- pre-school

- primary, secondary and tertiary phases

- higher education (which would be returned to the commons)

- other opportunities for learning throughout life.

Such a model of educational reconstruction will also set an example for others.

Thus this essay affirms its premises and shares Roth's conclusion that "we can change (the world) for the better, based on education, based on concern, and based on values that we share" [14].

We can also discuss it further here.

[edit] References

1a Fellows, N. (2017) 'What are social goods? What is the commons?', extremelyprovocative.com

1b Fellows, N. (2017) 'What are social goods? What is the commons? (2)', extremelyprovocative.com

2 Wesleyan University (2014) Introduction: Social Good and Tragedy of the Commons

3 Wikipedia (2017) Lists of schools in England: East Midlands

4 School Cuts (2017) School Cuts

5 Wikipedia (2017) Tuition fees in the United Kingdom

6 Wesleyan University (2014) Genealogy of the Idea of Social Good

7 Her Majesty's Government (1944) Education Act, 1944

8 Her Majesty's Government (1963) The Robbins Report

9 Fair Funding For All Schools (2017) Fair Funding For All Schools

10 National Union of Students (2017) Student funding: email your MP

11 Her Majesty's Government (1943) Educational Reconstruction

12 Her Majesty's Government (1988) Education Reform Act, 1988

13 Wikipedia (2017) Universal access to education

14 Wesleyan University (2014) Listening to the Local and Practical Idealism

[edit] Further Reading

Bollier, D. (2011) 'Ugo Mattei on the Commons, Market and State', bollier.org, 29 July, 11.26 BST.

Sanchez, J. (2021) 'Architecture for the Commons: Participatory Systems in the Age of Platforms', Routledge, London.

Unattributed (2023) 'Commons', Wikipedia.

Walljasper, J. (2010) 'All that we share : a field guide to the commons', Perseus, New York - on the Internet Archive.

--Archiblog 12:07, 10 Oct 2023 (BST)

Featured articles and news

Professional practical experience for Architects in training

The long process to transform the nature of education and professional practical experience in the Architecture profession following recent reports.

A people-first approach to retrofit

Moving away from the destructive paradigm of fabric-first.

International Electrician Day, 10 June 2025

Celebrating the role of electrical engineers from André-Marie Amperè, today and for the future.

New guide for clients launched at Houses of Parliament

'There has never been a more important time for clients to step up and ...ask the right questions'

The impact of recycled slate tiles

Innovation across the decades.

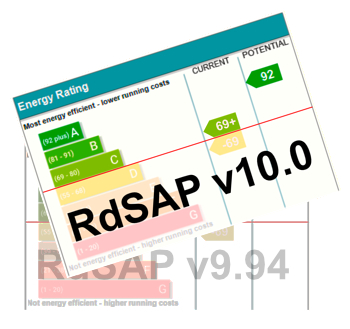

EPC changes for existing buildings

Changes and their context as the new RdSAP methodology comes into use from 15 June.

Skills England publishes Sector skills needs assessments

Priority areas relating to the built environment highlighted and described in brief.

BSRIA HVAC Market Watch - May 2025 Edition

Heat Pump Market Outlook: Policy, Performance & Refrigerant Trends for 2025–2028.

Committing to EDI in construction with CIOB

Built Environment professional bodies deepen commitment to EDI with two new signatories: CIAT and CICES.

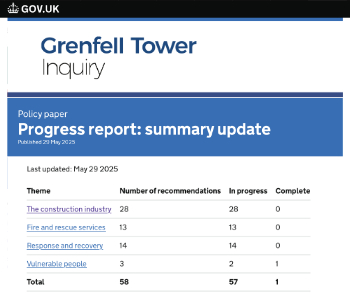

Government Grenfell progress report at a glance

Line by line recomendation overview, with links to more details.

An engaging and lively review of his professional life.

Sustainable heating for listed buildings

A problem that needs to be approached intelligently.

50th Golden anniversary ECA Edmundson apprentice award

Deadline for entries has been extended to Friday 27 June, so don't miss out!

CIAT at the London Festival of Architecture

Designing for Everyone: Breaking Barriers in Inclusive Architecture.

Mixed reactions to apprenticeship and skills reform 2025

A 'welcome shift' for some and a 'backwards step' for others.