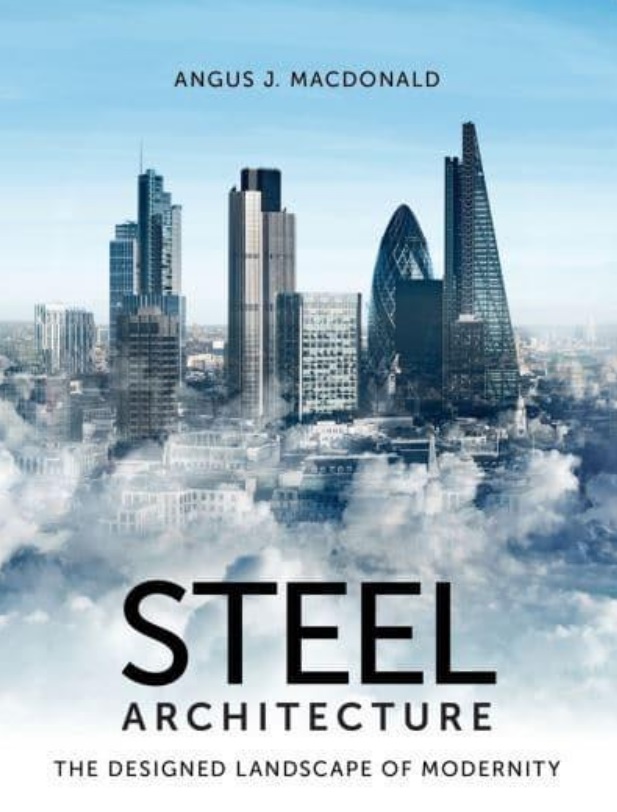

Steel Architecture: the designed landscape of modernity

Steel Architecture: the designed landscape of modernity, Angus J McDonald, Crowood Press, 2021, 160 pages, colour and black and white illustrations, hardback.

This book by a leading Scottish academic and professor of architectural structures is not, as might be anticipated, a survey of steel architecture. While it does briefly explain the origins of ferrous materials and the development of steel for use in architecture, the author’s principal objective is to question the way in which steel as a structural material was and still is being exploited by modernist architects for formalistic rather than functional ends. To present his case, he selects certain building types involving steel construction and sets them in the context of modernist ideas to reach a critical understanding.

His argument is that whereas in the early decades of the 20th century a steel framework was chosen for its strength and practicality, such as for the erection of tall buildings in the USA, from the post-war period onwards steel was frequently used by modernist architects solely for its aesthetic potential. For example, McDonald claims that Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House and Philip Johnson’s Glass House were intended primarily to establish a new vision of what a house should look like, while largely ignoring the practicalities of habitation in a glass box and the poor durability of minimalist fabric.

In the case of skyscrapers, where practicality had been the determining factor in their structural form for the first 100 years, the development of more sophisticated technology in the late 20th century, combined with a movement away from rectilinearity, led to the current fashion for oddly shaped and wacky designs. Here McDonald cites the China Central Television HQ, Beijing, by OMA and Rem Koolhaas, which uses extreme quantities of steelwork to create a distinctive shape that is nonsensical structurally. Likewise, he questions ‘high tech’, the style that emerged with the Pompidou Centre. The style was heralded as honest in displaying the steel structure and service elements, yet it was wasteful in its use of natural resources and expensive to maintain.

The most severe criticism is reserved for those buildings that are currently featured in the media and win international awards, such as the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, by Frank Gehry and the Riverside Museum, Glasgow, by Zaha Hadid. Although steel plays a vital role in supporting such buildings, their designers disdain the idea that the structure should be part of the visual language, and they hide the complex and inelegant array of steelwork within their fantastic curvilinear casings. Essentially, these buildings have been designed to stand out from their surroundings rather than be sympathetic to their context; formalist in nature, they disregard the need for programmatic function and careful use of resources.

In conclusion, McDonald draws attention to the demands of the climate crisis and suggests that steel architecture, which relies on one of the most polluting construction materials on earth, may have a limited future. He might have added that this in turn raises the question of how such buildings, which are sure to be considered as significant in architectural and historic terms, might be conserved in the future.

This article originally appeared as: ‘Supporting role’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 173, published in September 2022. It was written by Peter de Figueiredo, reviews editor for Context.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, or to suggest changes, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.