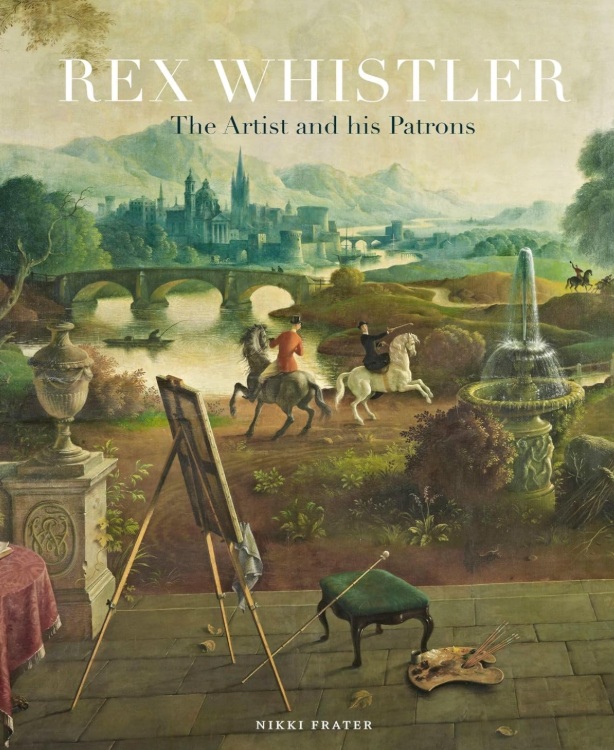

Rex Whistler: the artist and his patrons

Rex Whistler: the artist and his patrons, Nikki Frater, Paul Holberton Publishing, 2024, 191 pages, black-and-white and colour illustrations.

Published to accompany the exhibition held at the Salisbury Museum from May to September 2024, this book is a richly illustrated and informative guide to the life and work of a highly original English painter of the first half of the 20th century. Rex Whistler’s murals carry the viewer into a world neither real nor fancy but something in between. Men and beasts coexist in landscapes and seascapes with mountains in the background under infinite skies.

Born in 1905, Whistler was killed in action in the Battle of Normandy in 1944. His life and career in art were thus violently cut short, just as his close contemporary, Francis Bacon, was about to begin on route to the creation of his own unique paintings.

Moving on to the 1970s, we can record the work of Francis Haskell (1928–2000), the art historian who introduced to the English-speaking world via his publications and teaching the notion of ‘reception history’. Although his chosen field was the 17th century in Italy, Haskell showed with admirable clarity and much research conducted into unpublished sources, such as letters, bills and receipts, how art arises (in buildings, statues and paintings): it is as much from the individuals who commission as from the creative genius of those who execute the work. Up to this time the history of art had focused mainly on the artists and their lives, in a tradition that began with Giorgio Vasari’s famous Lives of the Artists (1550).

Nikki Frater gives us plenty of detail about Whistler’s training and the rapid development of his art, from his emergence in 1925 until he joined the army in 1940 when he still was able to finish some paintings. In addition, Rex Whistler: the artist and his patrons provides us with a full account of how, as an artist almost wholly occupied on mural decoration, he relied on admission to the wealthy homes where he spent countless hours adorning dining rooms, drawing rooms and stairwells. To grant access to domestic interiors of such importance, and to begin lengthy campaigns of work on their walls, clearly required much confidence on the part of the patrons and a suitable attitude of obedience to their whims and preferences on the part of Whistler. Although there were ups and downs, the artist made a success of this and established his lasting reputation.

Other books exist about much of this and the select bibliography gives generous details of them. Frater takes us through more than a dozen opulent London homes and superb mansions in the country within which Whistler’s creations are to be found. The illustrations are excellent and the whole effect is to encourage the reader to make visits (especially to such National Trust properties as Mottisfont Abbey near Romsey, Hampshire) to view how the artist was able to create both landscapes and architectural set-pieces, and the figures that inhabit them, on flat walls, while maintaining the illusion of deep space.

Whistler was by no means the only muralist working in the 20th century. Many theatres, cinemas and county halls in the UK were decorated on the grand scale by artists working at about the same time, including Henry Bird of Northampton, Eric Ravilious, John Piper and Edward Bawden. Mexico had its influential socialist mural painters such as Diego Rivera, while fascist Italy produced right-wing propaganda in public buildings in a genre that owes its historic origins to the distant past. Such a link with the past is demonstrated in West Sussex at the Church of the English Martyrs in Goring-on-Sea, where the ceiling was decorated with a scaled-down version of the Sistine Chapel ceiling by a parishioner, Gary Bevans, in 1987.

For the upper-class country house owners who engaged Whistler, his mural or ceiling paintings had a permanence and an inescapable presence that placed them in contrast to the nature of easel paintings, which may pass from one setting to another, sometimes becoming mere chattels. Pictures in frames were often looked down on, even regarded as bourgeois. Nikki Frater’s book has much to offer to readers who wish to learn more about the manners, tastes and foibles of these patrons, prominent members of the smart set in the 1920s and 30s, and about Whistler’s remarkable murals themselves.

This article originally appeared as ‘Painter to the smart set’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 181, published in December 2024. It was written by Graham Tite, a heritage advisor based in Sussex.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Conservation.

- Bas-relief.

- Clovelly, a village changing hands and changing with the times.

- Conservation.

- Fresco.

- From royalty to retrofit; sustaining the culture and condition of a historical rural village.

- Heritage.

- Historic environment.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Listed buildings.

- Murals.

- Trompe l’oeil.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?