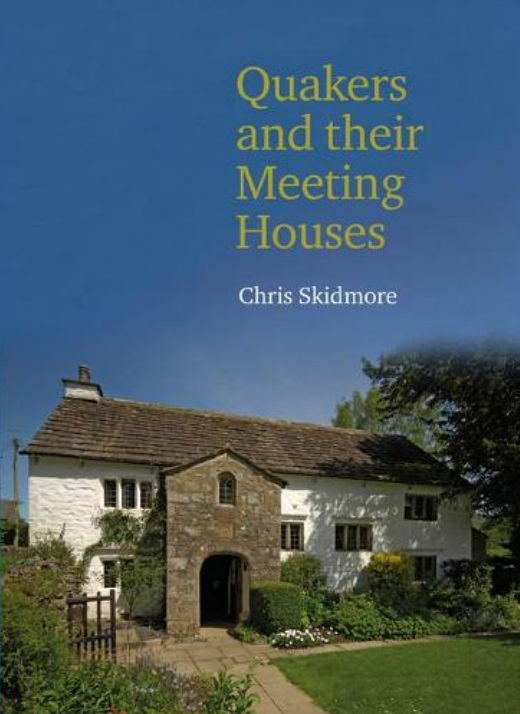

Quakers and their Meeting Houses

Quakers and their Meeting Houses, by Chris Skidmore, Historic England/ Liverpool University Press, 2021, 163 pages, 28 black and white and 188 colour illustrations.

We cherish Quaker meeting houses as ‘buildings of endearing simplicity’, for their social history or spiritual significance, or for architecture reflecting contemporary trends. Under threat as Quaker membership declines, we need to understand these buildings to inform conservation and decisions about disposal and change.

In 1999, David Butler’s two-volume gazetteer, Quaker Meeting Houses in Britain, was published, recording over 800 places ‘for which there is evidence of a Quaker meeting’. Between 2014 and 2016, the Quaker Meeting Houses Heritage Project, funded by Historic England and the Quakers, studied 345 meeting houses owned by Quakers and still in use in Britain (excluding Northern Ireland). Chris Skidmore, a member of Skipton Quaker Meeting and editor at the Chapels Society, has written a book that provides valuable synthesis of this study, brought up to date with recent meeting houses; Hammersmith opened in 2020.

With a useful introduction on the history of Quakers, the book provides excellent summaries of the role of George Fox and early Quaker evangelism, state persecution and toleration, Quaker beliefs, how meetings and the Society of Friends were (and are) organised, including the role of women. The book is arranged chronologically, illustrated with examples of meeting houses and ancillary buildings such as stables and (a new one for me) temporary meeting ‘booths’. Quaker meeting houses in America are also referred to, along with outdoor meeting places, burial grounds and Friends House, London. The final chapter is a discussion of Quaker architecture and meeting house fittings, with some personal observations from the author. Is there a defined Quaker style? 17th- and 18th-century meeting houses were fairly consistent in their planning and aesthetics (with regional variations), but once architects were involved, architectural diversity increased and diluted earlier distinctiveness.

The book is not a gazetteer of meeting houses, so David Butler’s books, which include a plan of every building, are still essential. For more detailed information on meeting houses, the 2014–2017 reports compiled by AHP with input from Quaker volunteers are available online at http://heritage.quaker.org.uk. Skidmore’s book includes a gazetteer of listed meeting houses, but this is not comprehensive; it includes all Grade I and II* buildings, but only Grade II listed buildings referred to in the text, along with some former meeting houses, such as Cartmel Height, now a dwelling. In 2019 11 meeting houses were newly listed at Grade II and six were upgraded to Grade II* or Grade I.

Generously illustrated, well produced and written in an accessible style, the book is a pleasure to read. There is a useful glossary of architectural and Quaker terms. A few more plans, particularly to illustrate early meeting houses such as Brigflatts, would have been useful, but plans can be found elsewhere.

This article originally appeared as ‘Endearing simplicity’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 173, published in September 2022. It was written by Marion Barter, a buildings historian, who led the Quaker Meeting Houses Heritage Project while at AHP.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Conservation in the heritage cities of Venice and Liverpool.

- DCMS Culture Secretary comments on HM Government position on contested heritage.

- Diversity.

- Equity, diversity and inclusion in the heritage sector.

- Ethics.

- Heritage asset.

- Heritage.

- How architecture can suppress cultural identity.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Queer Spaces: an atlas of LGBTQIAplus places and stories.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.