Donald Buttress

Donald Buttress, Kenneth Powell, with an introduction by Matthew Saunders, Shaun Tyas, 2022, 232 pages and 263 illustrations, hardback.

|

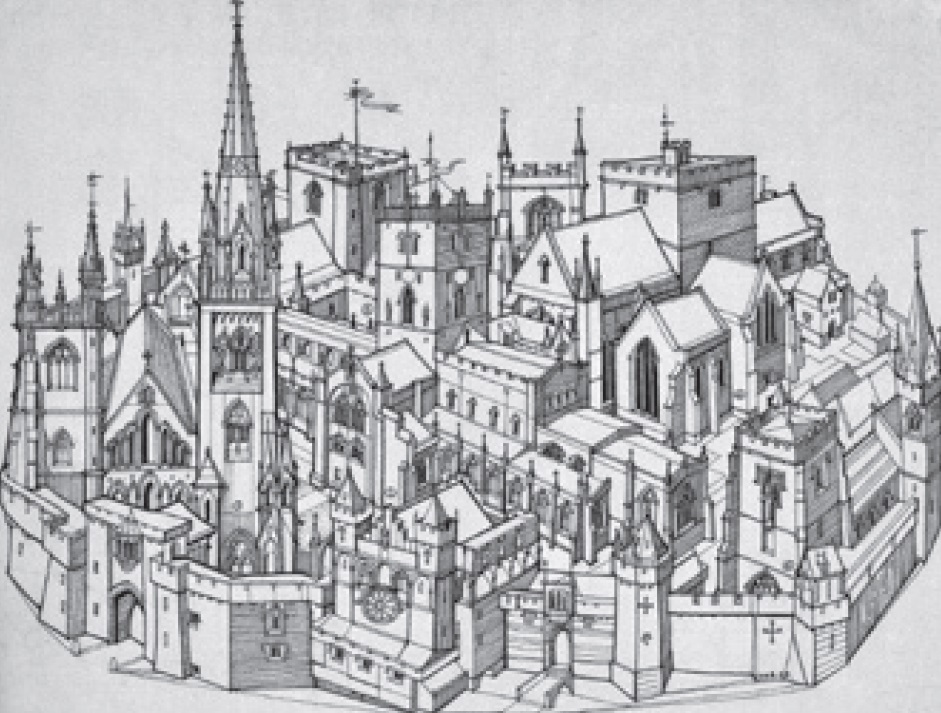

| A pen-and-ink capriccio by Donald Buttress of the six ancient cathedral churches of Wales (Llandaff, St Asaph, St Davids, Bangor and Newport) in an imaginary medieval enclosure. |

It was a lucky chance that in the 1970s Donald Buttress, a founder member of the Victorian Society’s Manchester Group, travelled to Leeds to speak to the new group there, and met Kenneth Powell. With the connection lasting some 50 years, they have now given us an important book commemorating Donald’s life and work.

Buttress grew up, trained, worked and taught in Manchester, and was steeped in its Victorian inheritance. From school days onwards he showed considerable draughtsmanship and skill for design. Having acquired huge knowledge of architectural history, his career took off. With a teaching post at the university and a burgeoning practice in the city, his love of medieval architecture led him to early appointments to cathedrals, including Llandaff, Chichester and, later, Westminster Abbey and his move south.

I was lucky to encounter Buttress in my early student years in Manchester. Livelier and more colourful than many colleagues, I remember especially the visits made: to his house at Hirnant in Wales, the journey one of continuous and informed commentary on the churches and houses we passed, to Haddenham in Buckinghamshire, the courtyard home of his contemporary, Peter Aldington, and to churches in Manchester which Buttress had repaired, and adapted or extended. He encouraged us to look at vernacular buildings and to design in keeping, and he set us a project for a new house in the country. Ultimately he preferred the solution of one of my fellow students: a considered glass box, to the more hesitant and perhaps feebler designs of the rest of us.

Buttress’s boldness is clear in his drawings, which are so beautifully reproduced in this handsome book. His simplified strong block prints, university and National Service posters, sit alongside miraculously realised drawings of Italian churches and medieval architectural fantasies. They mirror his bold approach to the care and development of old buildings. ‘What I have tried to do all my life – to learn about a building, its history and its purpose and yes, of course, to conserve where conservation serves a practical purpose, but to be bold in keeping the building alive and fit for purpose… (to) preserve it for the future where additions will simply become part of its history.’

That view, which comes straight from his Victorian heroes, often set him up against the amenity societies and planners. Perhaps because few of them had his deep knowledge of the history of architecture, and even fewer his design skills, they were wary of his bold proposals. But the chapters in this book which illustrate his new work, from the simple early schemes in the north of England, to later work in rebuilding Tonbridge School Chapel and St Matthew Westminster, are a vindication of his approach. The latter two, shown in detail here, demonstrate Buttress’s command of style and detail, from the overall scheme down to the design of furnishings, memorials and fittings.

His work in repairing buildings is more complex. His enthusiasm for George Gilbert Scott’s All Souls, Haley Hill, and his belief that the condemned spire could be saved, proved right. Working with Arup to design an internal brick lining, he saved what Scott himself had described as ‘on the whole, my best church’. Buttress was as vigorous in his approach to stone repairs and replacement as he was in design, sometimes leading him into controversy. Difficulties at Chichester are covered carefully by Powell, and well illustrated. Similarly, the renewal of work at Westminster Abbey is shown in photographs and drawings. There were many opportunities for gifted sculptors and carvers, and Buttress rebuilt many features using Portland stone, replacing earlier and softer Bath-stone details.

We are lucky that Buttress, with his deep knowledge and understanding of historic buildings, was able to do so much. He could be described as ‘the last of the Victorians’: an inadequate description but one which is a cause for regret, as the disciplines of archaeology, art history and architecture diverge. We are unlikely to see another such confident and creative architect working on our cathedrals, but Kenneth Powell’s book has made sure that his story will be available to inspire future generations.

This article originally appeared as ‘Nominative determinism’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 176, published in June 2023. It was written by Jane Kennedy, a former cathedral architect.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.