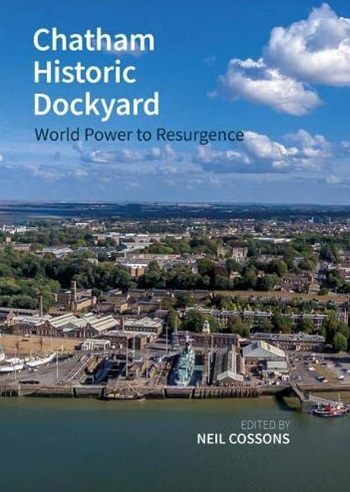

Chatham Historic Dockyard: world power to resurgence

Chatham Historic Dockyard: world power to resurgence, Neil Cossons (editor), Liverpool University Press for Historic England, 2021, 136 pages, 18 black and white and 84 colour illustrations.

To many people the former Royal naval dockyard at Chatham plays second fiddle to better-known Portsmouth and Plymouth. However, unlike its south-coast cousins Chatham has been a wholly redundant naval base since its closure in 1984. To those who know their history, Chatham’s slow decline in the 19th and 20th centuries is in part due to a shift in threat from mainland Europe – from the French, and especially the Dutch who notoriously sacked the fleet at Chatham in 1667, to the Mediterranean seaboard and then the Atlantic.

After nearly 40 years since its closure, it is instructive to look back at how this once premier facility has survived and turned itself into a successful heritage site, celebrating what has been described as ‘the most complete dockyard of the age of sail’. For that is the importance of Chatham – sail, not steam, diesel or nuclear power. Its final, somewhat ignominious years were given over to the maintenance of the nuclear submarine force.

This is a slim volume but none the worse for that. Beautifully illustrated with both contemporary photographs and a wealth of sometimes breath-taking archival material, it is composed of six substantial essays by experts in the subject area such as historians Andrew Lambert and Jonathan Coad, and key heritage professionals involved over the last 40 years. These include Richard Holdsworth, who joined the dockyard trust as curator in 1985, Paul Hudson, who has overseen the development of those parts of the wider dockyard where development was envisaged, and Paul Jardine, who writes knowledgeably from the National Lottery Heritage Fund’s position.

All the essays repay careful study, and give a good overview of the social, economic and political issues involved in the ‘resurgence’. Expertly, and (given his work at the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust) appropriately edited by Neil Cossons, the book ably demonstrates best practice in seeking to conserve so large a site. Wholeness is all with large complex military (and civilian) sites such as Chatham. Think of what has been lost through the dissolution of such historic sites of even relatively recent times such as Croydon Airport, Trafford Park or the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley.

Overall, the point of this book is not simply to revisit the history of Chatham dockyard and its buildings since their Elizabethan origins – that has already been ably done by Jonathan Coad’s Support for the Fleet – but to learn how to protect and project that history after 1984. The first and foremost lesson is to try to maintain the wholeness of the site. Even here that has not been possible, and decisions were made to save what represented the ‘age of sail’ at the expense of the age of steam and diesel. Another of the lessons is to have friends in high places, and with access to large funds.

Even then, with one of the largest grants ever awarded, the future of Chatham has been financially tempestuous. Perhaps the most important lesson is to have a willing director of planning on side. That came in the shape of Kent County Council’s Harry Deakin, clearly a man with vision. The book should be required reading for anyone faced with the disposal and/or redevelopment of large complex sites. We could do with more such exemplary studies.

To end on a personal note, when the docks closed in 1984 the entire Medway towns went into shock. Some of the skilled civilian staff took the opportunity to retrain in the local art college, Medway College of Design, especially in the silversmithing and jewellery department. Having been a young lecturer there at the time, it is sad to learn that the college, its late 1960s design modelled partly on Fort Pitt, one of the chain of artillery fortresses built to protect the dockyards, is itself now due to close.

This article originally appeared as ‘The age of sail’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 173, published in September 2022. It was written by Julian Holder, a senior associate tutor in architectural history at the University of Oxford and director of graduate programmes at the Weald and Downland Museum.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, or to suggest changes, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.