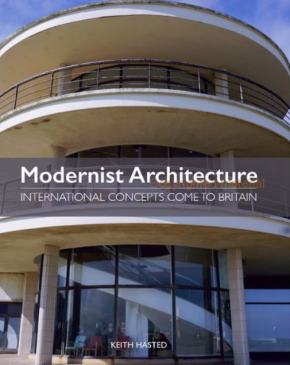

Modernist Architecture: international concepts come to Britain

Modernist Architecture: international concepts come to Britain, Keith Hasted, Crowood Press, 2019, 158 pages, 152 colour illustrations and line drawings.

Over many years writers have explored the sources for British architecture and design in the 20th century, citing the interplay of native traditions and the international modern movement to produce a range of modernisms. Nikolaus Pevsner’s ‘Pioneers of the Modern Movement’, published in 1936, championed modern architecture, the genesis of which he traced back to Pugin, Ruskin and William Morris, via Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus, which he linked with values of truth, honesty and faith in technology. In 1977 David Watkin launched an attack on Pevsner and the notion that ‘modern’ and ‘good’ were synonymous; while subsequent architectural historians, including Alan Powers, have shown how British modernism has been at its most radical when ethical values such as compassion and conscience have been at the forefront, rather than aesthetics.

Keith Hasted, author of ‘Modernist Architecture’, avoids these theoretical concerns of 20th century architects and their clients, and focuses largely on matters of style, seeking to identify aspects of modernism abroad that have influenced British architecture. He starts with the Chicago School of the 1890s, moving on to Frank Lloyd Wright, followed by Europe between the world wars, and ending with Mies van der Rohe in the USA. The chapters on America and Europe are interspersed with ones that trace developing trends in British modernism from Norman Shaw and Lutyens to Wells Coates, Lubetkin and Erno Goldfinger; the final two chapters include the Festival of Britain, brutalism, Coventry Cathedral and Bankside Power Station, Miesian purity, post-modernism, high tech, neoclassicism and deconstructivism.

The task of covering so many buildings and architects in a slim volume means that there is little scope for analysis. Familiarity with un-illustrated projects is taken for granted, and there is often no explanation why buildings that are featured have been chosen to advance the author’s case for international influence. Japan, Scandinavia, Italy and South America get no mention. Many architects make an appearance, and each one who is mentioned is afforded two or three sentences telling us when and where they were born, which architectural school they attended and the highlights of their career. This interrupts the flow, giving the book a repetitive form that could have been avoided by the use of an appendix. The illustrations, apart from the author’s skeletal drawings, however, are generally informative.

Britain remains a culturally conservative country, where modernism is still treated with hostility, and it was John Summerson’s view that British culture needs a periodic injection of foreign logic to stimulate original thought and debate. Keith Hasted’s book presents a wide range of buildings that have undoubtedly influenced British modernism, but without the shifting background of social, political and economic concerns, its contribution to a deeper understanding of British modernism is limited.

This article originally appeared as ‘Slim Pickings’ in IHBC's Context 164 (Page 53), published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in March 2020. It was written by Peter de Figueiredo.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?