A brief history of the CPI conventions Appendix 1

This is Appendix 1 to A brief history of the CPI conventions.

Click here for Appendix 2.

The guidance in more detail:

First editions - 1987.

There were initially two basic designations of ‘CPI’ documents:

- Those produced completely under the control of (then) CCPI called ‘CPI documents’ and bearing a very large CPI logo.

- Those produced by others in close coordination with CCPI called ‘CPI coordinated documents’ and bearing a small CPI logo alongside their titles.

This distinction was particularly important in the case of the Standard Method of Measurement evolving editions (1 through 6) and which had been published since the 1920s. Later, whilst the technical and legal distinction still existed the application of logo size gave way to cover artwork more contemporary with other publications of the time.

A common thread through all the documents is that production information must be complete, precise and clear to the users of that information and not merely convenient for the producer which research revealed has been a characteristic that typified much of the bad or poor practice.

SMM7 a CPI coordinated documents presented in two parts:

- Standard Method of Measurement of Building Works Seventh Edition.

- SMM7 - Measurement Code.

Whilst the drawings are generally reckoned to be at the heart of describing a construction project and so the most logical starting point, the need for a new Standard Method of Measurement had been recognised years before and as it was an established document with a secure publishing ‘home’ (RICS and [the then] NFBTE [1] ) and used since 1922 in construction contracts, let us consider that first.

SMM6 had incorporated some of the recommendations of a report from Reading University for the SMM Development Unit to replace the, by then, very creaky but comfortably familiar to quantity surveyors, SMM5 but in response to demands from the sector it had been rather rushed out before the job was complete. Hindsight being what it is, this proved fortuitous for the coordinated work just kicked-off under CCPI. One of the areas of struggle that had been contentious and not resolved in SMM was the breakdown of trade (or other such as proposals for elemental) sections. SMM6 (1979) therefore inherited a breakdown with only minor updates from SMM5 which itself would have looked familiar to a practitioner from 1922, as one commentator put it “SMM6 continued to represent a fairly accurate picture of 1920s construction trade practice”.

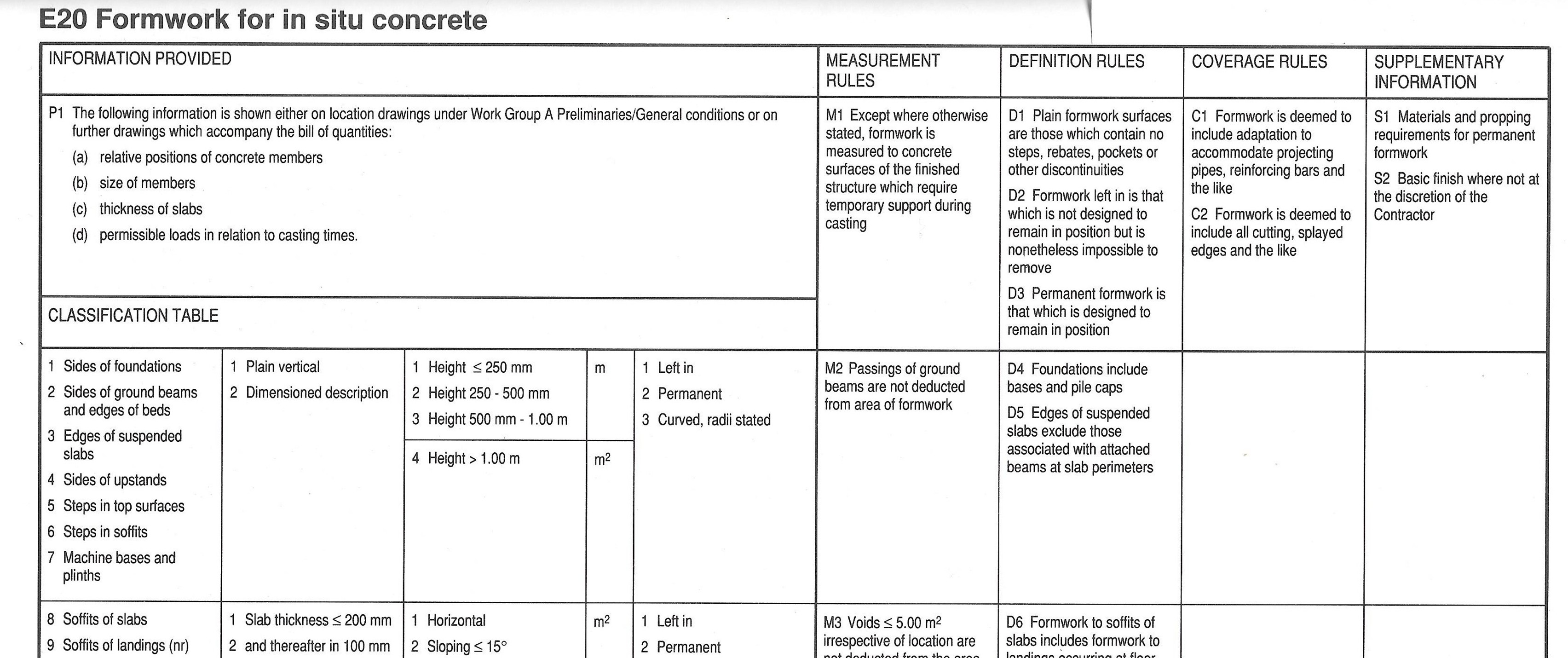

The format of SMM7 differed significantly from any of its predecessors with the most significant change being that it benefited from being able to adopt a breakdown from the CCPI work on the Common Arrangement of Work sections (CAWS). CAWS worked well with the other major format change and that was to a tabular and cascading arrangement of the information rules across a broad (landscape) page with a main table per CAWS section covered. Document 1 of the pair.

Document 2 was drafted in a similar style and format to the codes for drawings and specification and contained the measurement rules to be followed.

The presentation changes also created unintentional advantages to others on the construction team. By working across clear tables describing well defined packages of work anyone in the team could quickly see the requirements in terms of:

- information provided (in terms of reference drawings, schedules and/or specifications with an almost clairvoyant nod to what, with BIM, has become ‘level of definition’)

- measurement rules

- definition rules

- coverage rules and

- supplementary information.

This was particularly useful in, for example, preliminary assessment of contractor’s claims. Whilst the formal job would remain within the Quantity Surveyor’s expertise, an architect or other certifier could very quickly and simply check if a claim seemed to have substance and prepare for it ahead of the formal recommendations from the QS. Previously other participants had viewed the SMM as a manual to a mysterious art of interpretation. There were other changes and developments in SMM7 over its predecessors mostly enabling better alignment with contemporary legal contract and subcontract practices in the 1980s.

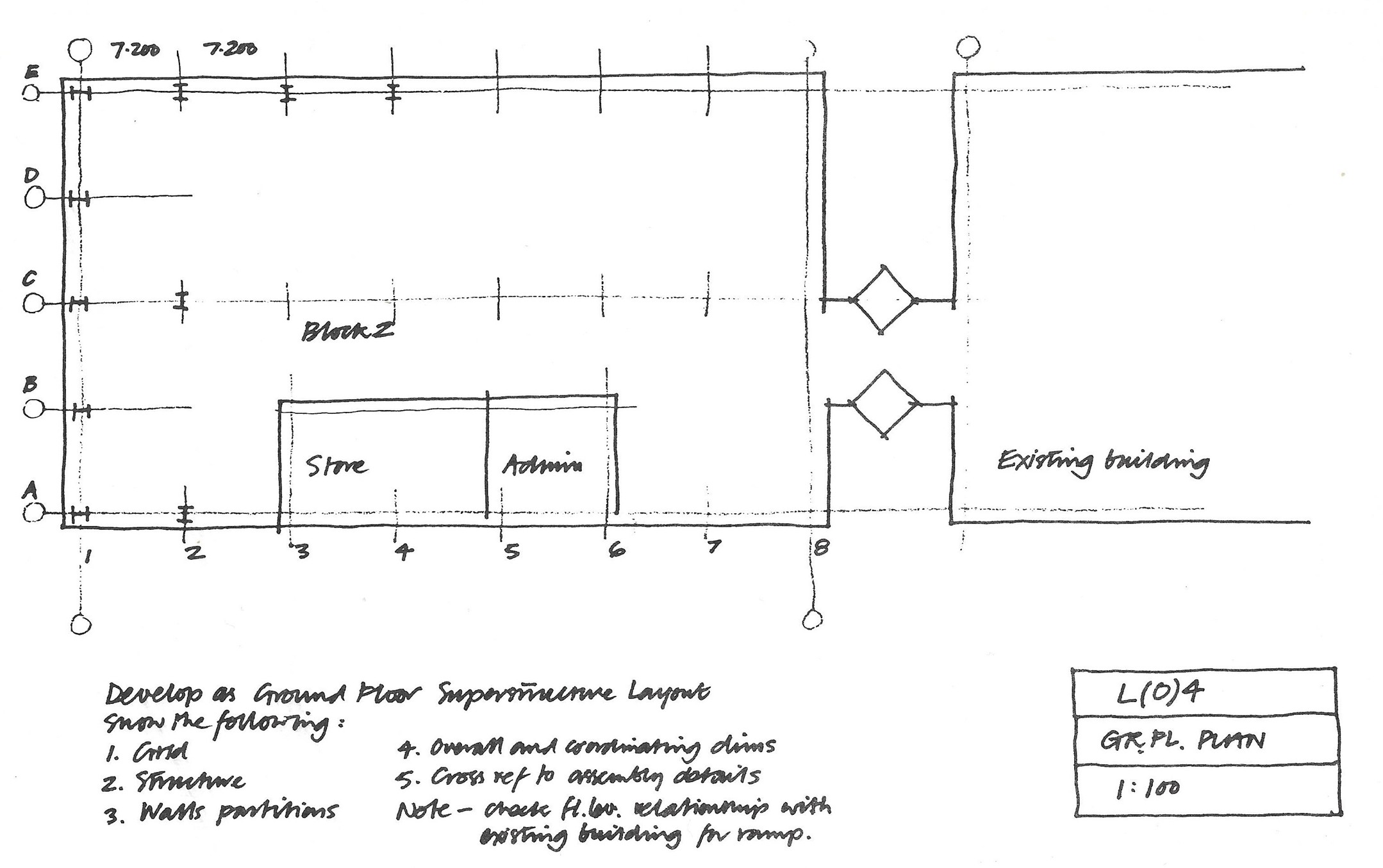

As well as the tabular layout, there were now express requirements for drawn information such as block plans site plans and representative plans sections and elevations showing the position of spaces, general construction and main elements within the Preliminaries and General conditions (CAWS section A). Whilst sometimes done this was never previously an express requirement.

For the particular work sections requirements for supplementary drawn information were also included and for convenience all the requirements for drawn information are also given in an appendix to the Drawings Code.

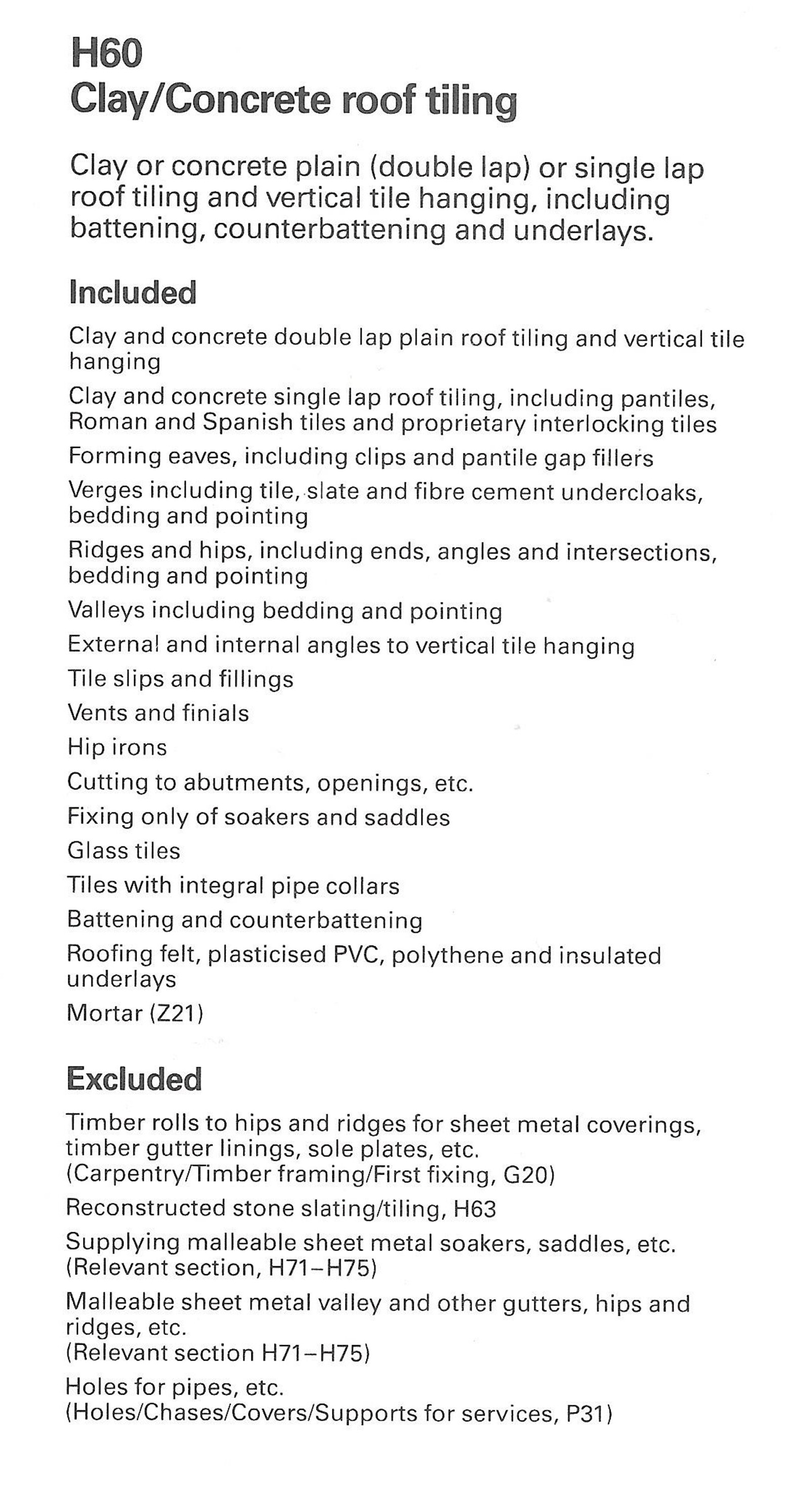

The rules for Bills of Quantities clearly link through the use of CAWS work section codes (e.g. E20 above) and the link goes to the level of phraseologies and content such that between them the full specification description occurs in the specification document and the bill item only need use enough description to allow pricing. Invariably full specification information is not available for all the work at ‘bill stage’ or even within tender information, but the tight cross referencing and single source principle allows far more certainty. It is clear where the accurate information is available and also clear and direct when certain detail is not available. Subsequent valuations during construction can be more speedy and cause fewer, and hopefully no, disputes regarding type, quantum and value adjustment in-line with the, by now available, production versions of drawings, full specifications and, work measured on site.

CAWS – Common Arrangement of Work Sections for building works - a CPI document

The titles, the descriptions and terminology used throughout adopted a one term one meaning policy and benefited from guidance, mostly in the Specification code, that showed that semantic logic and consistency aided understanding if at times eschewing familiar but often imprecise jargon and custom.

Not created to be a classification system

CAWS was a view of contemporary working practices at the finest practical level matching real world practices, and not, of itself therefore a classification system. Among other attributes, classifications generally set out to be both comprehensive and perpetual - think for example of botanical classification. Being a snap-shot of mid the 1980s CAWS was expected be updated not only from feedback in use but from shifts in the sector, and particularly evolving sub-contracting, practices. Indeed it was updated (mostly extended) several times internally and, for users, advice was available by contacting CPIc. The original document was once re published as an updated version.

CAWS was specifically designed to allow drawings, specifications and bills of quantities, or other measurement/quantification methods, to align and cross refer using terms and description defined in one place. Any other uses were a bonus but only if they did not propose compromise to that purpose. CAWS navigated the myriad different terms and jargon so popular in construction using a consistent lexicon and the way it was structured automatically created an arrangement that, by extraction and compilation of complete sections, provided for the production of well fitting packages of information for pricing by sub-contractors and execution on site.

CAWS was eventually incorporated in two forms – for building and for civil engineering - into the first edition of Uniclass in 1997.

A second edition of the stand-alone CAWS publication was issued in 1998.

Project Specification - A code of procedure for building works - a CPI document

Separating full specification from measured items in Bills of Quantity was seen as one of the more revolutionary proposals in the CPI documents. Even the education of professionals such as architects and quantity surveyors to some extent reflected the bad practice in that many, if not all, degree courses in quantity surveying included lectures and examinations of specification writing whereas many architecture courses gave the subject scant attention. This was in part because the custom had developed of placing specification information with and within Bills of Quantity – sometimes labelled preambles - a document with contractual significance with regard primarily to pricing. Other – but by no means comprehensive and invariably inconsistent specification information was included in annotation and notes on drawings. The key to unlocking the mess is to see specification as wholly a creation of design activity, as are the drawings, wherein the detailed requirements of selection and quality are definitively spelled out and installation and construction requirements are clear. The Bills of Quantity (or other pricing mechanisms) can then refer to that authority, now using the CAWS codes, and not repeat or invent them. Similarly the drawings can become clearer with minimal specification annotation and mostly no need for specification notes.

The specification code is in three parts:

- General principles of specification writing

- Guidance on coverage

- Illustration of the use of libraries of clauses

It sets out to inform designers how to create specifications that are:

- specific to each project

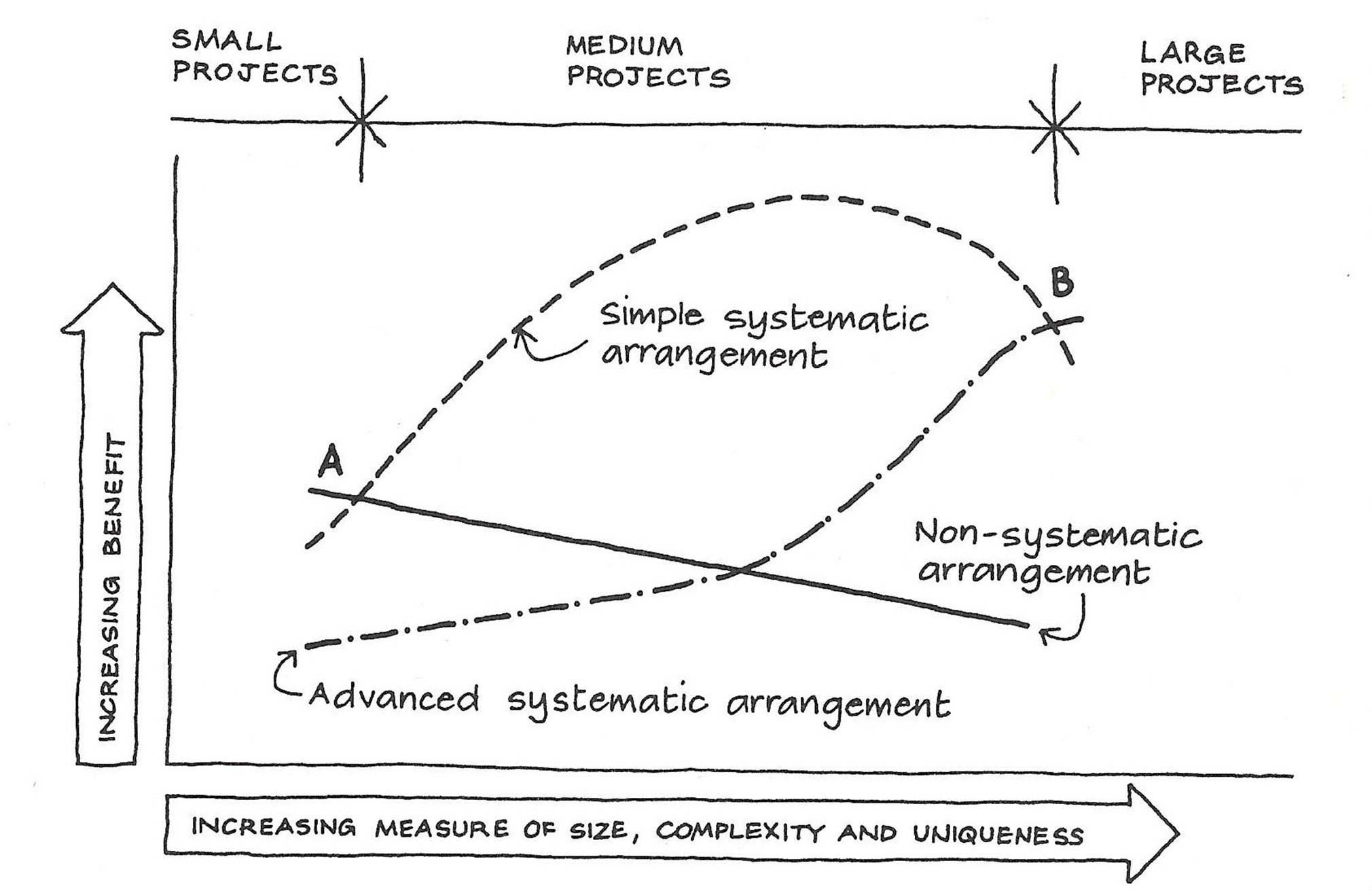

- appropriate to the size and/complexity of that project

- comprehensive

- without repetitions or duplications

- precise, specific and helpful

- clearly and concisely worded and instructional (direct)

- up to date

- enforceable

- searchable (using CAWS)

and avoid:

- any vagueness

- inappropriate references (e.g. to an esoteric foreign standard)

- indirect or passive language

- confusing performance and prescriptive clauses

- confusing reference and descriptive clauses

- ambiguous when allowing contractor choices

Picking a few of these.

Performance vs prescription: Some items suit specifying by performance, some by prescription and some a combination. A cladding system for example might most appropriately be specified by reference to the performance criteria to do with keeping the weather out, heat in and complying with appropriate regulations and standards etc. but the colour would normally be specified prescriptively. Alternatively the whole system could be specified prescriptively by saying the equivalent of “supply and fix Smiths cladding system xyz colour ‘azure’”. There are liability consequences also. Performance clauses place the onus on the supplier to comply with the performance requirements the onus on the designer is to give the correct references (but see note on reference vs description). Prescriptive clauses albeit often looking simpler place the entire onus on the designer i.e. for having satisfied themselves, and so taken-on the responsibility, that the “Smiths product xyz” is entirely appropriate in every respect for the proposed use. That said, the code points out that responsible design including specification should be geared towards increasing the likelihood of achieving the right result for the client and not about simply transferring responsibility and risk.

Reference vs description: Sometimes related to performance vs prescription, specifications invariably use many references such as to regulations, codes, standards and manufacturers’ literature. There is in the code one quite stark line on this that caused quite a stir albeit of the “embarrassed shuffling” kind at the time however, pointing out the then common bad (lazy) practice of including “blanket references” it said:

“Despite the inherent advantages, specification by reference is characteristic also of much bad practice in the use of blanket references to Codes of Practice which the specifier has not read, which the contractor will not have on site, and which in any case contain a variety of recommendations and options that ought to be decided upon by the designer.”

The Code elaborates on this noting that all references should be substantive, well understood, explicit and helpful. If only a part of a document is relevant, only that part should be referenced, if only a very small part consider if it is better to use the content in a descriptive way whilst bearing in mind that quoting large parts of authoritative documents is both inefficient and likely to create errors or contradictions. The ubiquity of and familiarity with such documents will also influence this decision. Absolutely not acceptable are terms such as “ …. to comply with all regulations and standards” or anything else that is not clear and explicit.

Finally the Code discusses the use of practice and proprietary specification libraries and shows particular examples provided by the National Building Specification (NBS), including the choices where a practice specific version of a proprietary system can be created perhaps limiting the choices for particular types of repeated work for example for school or hospital work. From an idea in the late 1960s, commercial launch in 1973 and computerisation in ~ 1980, by 1987 NBS had wide take up in architects’ practices and rearranging into CAWS sections to coincide with the launch of the CPI documents gave it a further boost. Just prior to the CPI launch the first editions of the CIBSE sponsored National Engineering Specification (NES) became available also.

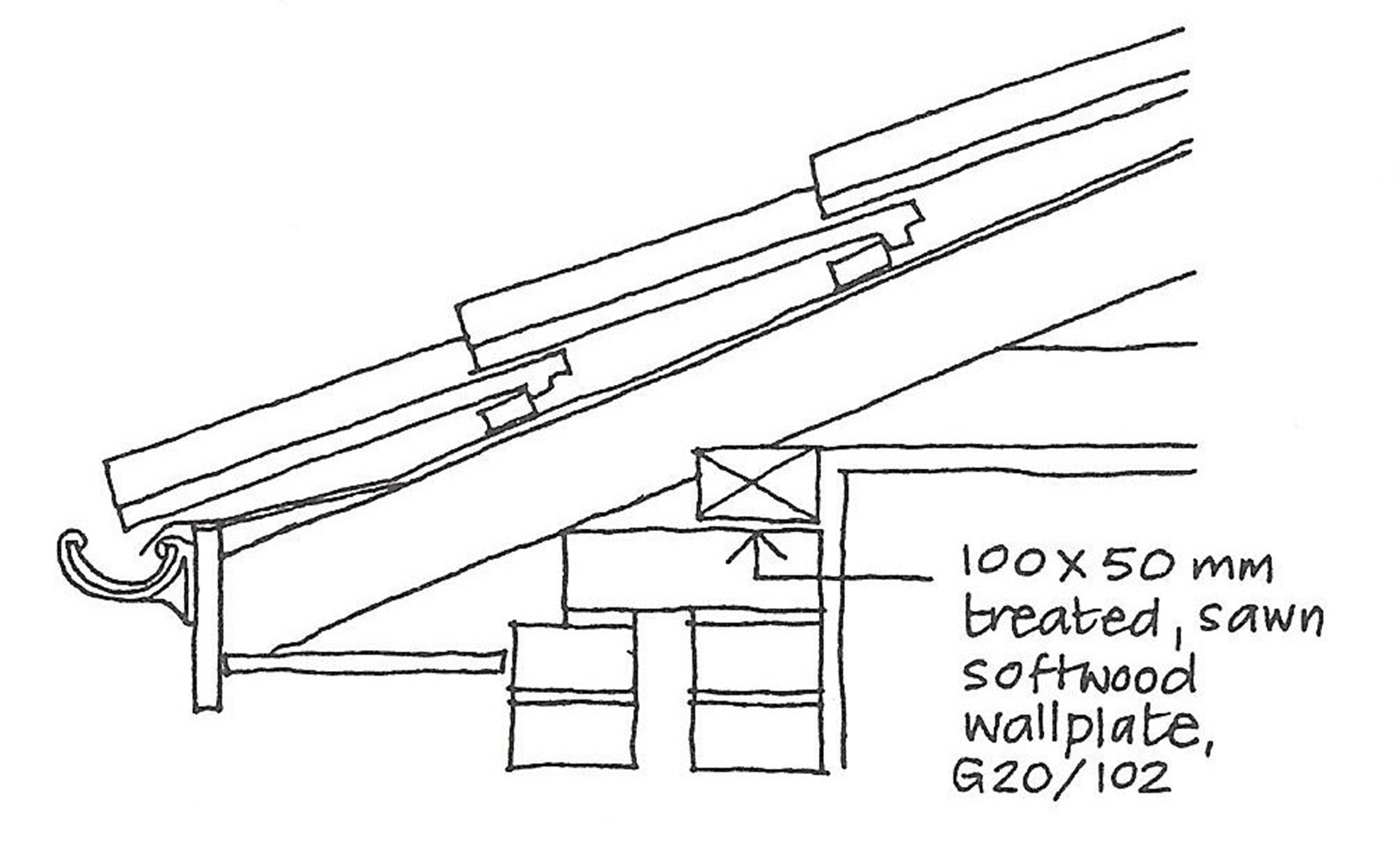

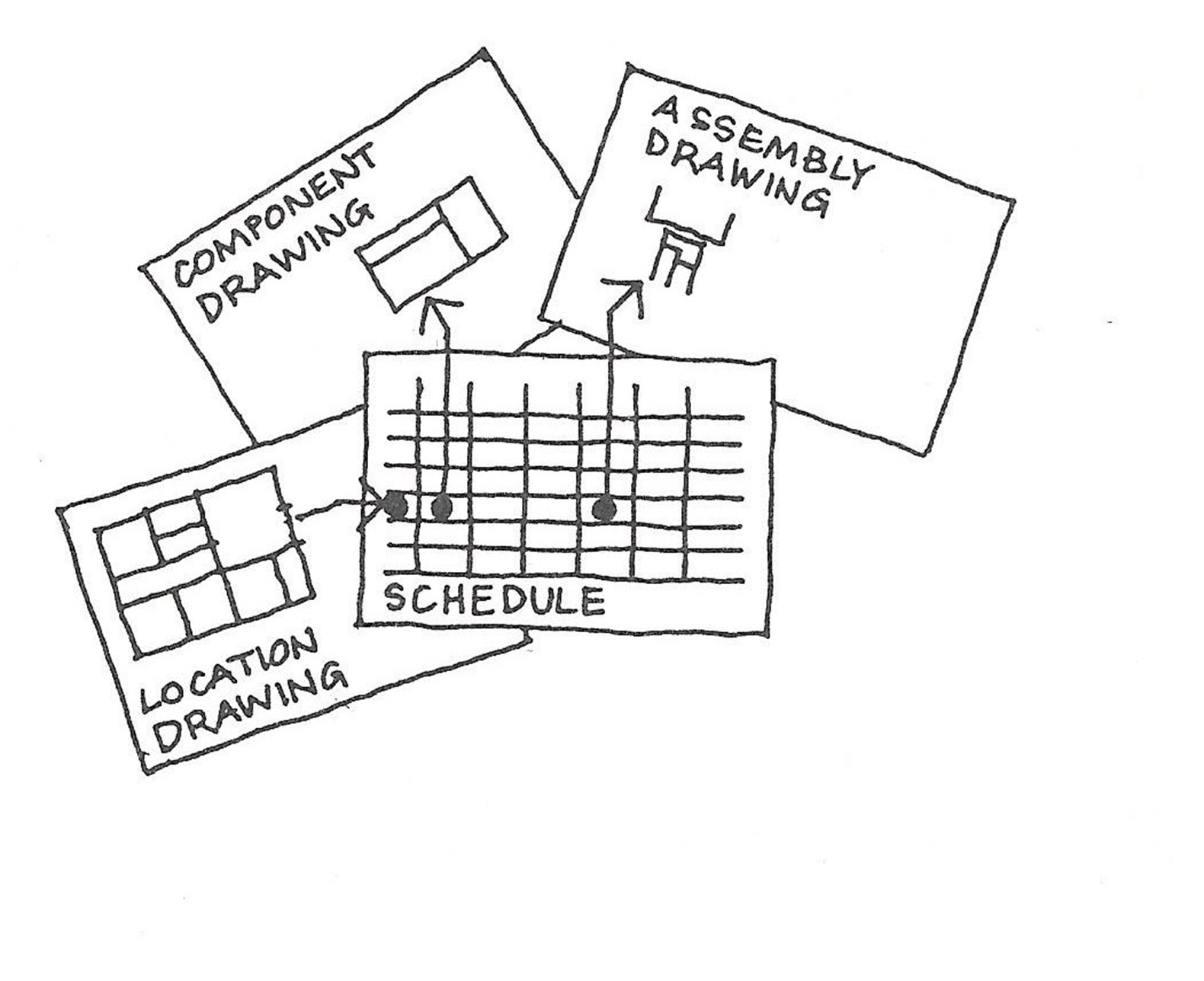

Production Drawings - A code of procedure for building works - a CPI document

Whether speaking to a lay person or an experienced construction person “the drawings” would be seen as the heart of the design process. Historically we have seen from the Lutyens quote (Part1) this was absolutely true with little other documentation typically evident and what specification there was contained in notes on the drawings. For the smallest of works – a small house kitchen extension for example this can still be true but, whilst maintaining their position as the ‘heart’ of the information matters are technically and legally more complicated now, illustrating design and construction graphically requires far more detail and so two fundamental roles of the sets of drawings in addition to showing the necessary graphical content is to be searchable within themselves and to relate directly to other documents – most importantly the text based specification.

The graph first emerged as a hypothesis very early in the research phase but from this it endured and was used as a vehicle in the Code to explain the vital role of arrangement such as: by discipline, by type of information and by element (part of the building/construction).

At the time the British Standard BS 1192:1984 Construction Drawing Practice was current and that had various topics with which the code aligned such as recommendations for sheet sizes and scales - important for reprographic and legibility functions of the time.

On drawing content whilst the Code points out the difficulty in such a document of being specific or comprehensive very useful principles are proposed, for example:

For any particular piece of work the drawings will need to give information about

- Shape

- Dimensions

- Position/orientation

- Composition/component parts

- Fixings

The code also emphasises that references should go from the general to the particular – a general rule but particularly so in set of drawings.

|

|

Finally, set out in CAWS order is a table of information to accompany bills of quantities at tender stage and on the best way to deal with drawn information on projects without quantities.

Other launch information

Other information issued at the launch was a booklet which initially had no cover price and was issued as a loss-leader “Co-ordinated project information for building works, a guide with examples”. This proved very popular and the first print run exhausted quite quickly. It was then re-printed and a small cover price applied to cover primarily admin and postage plus a small contribution to production costs although this was still mostly covered from sales from the formal documents.

|

|

A short run of promotional videos were also produced. This was 24 minutes long (though later a shorter version was also made and can be found digitally converted on the web). The video goes through the whole set of documents and features excerpts from the BRE, clients, designers offices and construction sites illustrating the operation of the principles of the codes and the advantages to all participants.

Both the booklet and the video bring together the findings of the 7 years of research at BRE into what happens to quality on site and the relevance in the CPI conventions in addressing many of the issues.

References:

- [1] National Federation of Building trades Employers.