Pier Paolo Pasolini

|

| ‘Untitled 1986’, otherwise known as the Headington Shark. |

‘Oh generazione sfortunata!’ proclaims the first line of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1970 poem ‘The Poetry of the Tradition’ – ‘Oh unlucky generation!’

Pasolini’s centenary in March was celebrated with much junketing in Italy and not much elsewhere, where he is mainly known for his films, now fading to dust in the world’s archives. His remarkable legacy of poetry has gained an Anglophone audience only recently, with Stephen Sartarelli’s scholarly 2015 selection, brought about with the aid of Pasolini’s fellow film-maker James Ivory.

One of the pillars of Pasolini’s work is tradition. Not the tradition of cheese-rolling, mayhem Shrovetide football or Up Helly Aa, but tradition deeply embedded in language and landscape. Much of his early poetry is in his native Friulian. He recognized the fundamental relationship between language and cultural identity that is now a widespread European movement, to the dismay of many nation-states.

Pasolini saw his poetry in the tradition of the Poesia Civile – Civil Poetry – of Dante and Boccaccio; shown by his frequent use of terza rima, and a triangular relationship between a personal viewpoint and two opposing imperatives. In Dante’s case these were the religious and moral, but to Pasolini they were deprecated politico-economic interests versus laudable ones of tradition or the needs of society.

My generation has been browbeaten with the notion that ours has been the most privileged in history. Despite a 50-year career in sustainability and conservation, it is disconcerting to read a poem written when it had hardly started describing us as unlucky for not ‘getting’ tradition. Pasolini correctly foresaw that all our mould-breaking new freedoms of the 1960s would merely lead to a lifetime of slavish consumerism.

In his lifetime Pasolini’s work met with critical acclaim, commercial success, and constant lawsuits brought by censors and self-appointed moralists. His hatred of clerico-political authoritarianism was as visceral as his loathing of the politico-economic hegemony which dogs us to this day. This standpoint was paralleled in Norman Jewison’s 1975 film ‘Rollerball’, set in an unregulated future in which nation states have been supplanted by multinational corporations who edit the world’s knowledge for their own ends. Sounds familiar?

The interface between regulation and tradition is an uneasy one, as conservation work often reveals. Confusion between paternalistic regulation, reviled by Pasolini, and ‘necessary’ regulation means that deregulators are apt to throw the baby out with the bathwater with reduced standards and underenforcement. This is brought home in the sharpest relief in Richard Norton-Taylor’s starkly moving play ‘Value Engineering: scenes from the Grenfell Inquiry’, which consists entirely of verbatim transcriptions of evidence given by participants in the inquiry. Its assembly into a succinct drama is far more telling than daily reports of minute detail over many months. At the end, appropriately without curtain calls or applause, one is left with the feeling that, notwithstanding the catastrophic sequence of individual failings, the real villain was the compartmentalisation of the procurement process that left no one with any connection to the project as a whole. It was a disastrous failure of regulation with no trace of the traditional processes, founded in those of craft guilds and the professions, in which the delivery of quality is holistic and carried out with pride.

‘Untitled 1986’, otherwise known as the Headington Shark, was a work of genius designed to make a Pasolinian political point in such a way as to be certain of producing public censure. Oxford City Council duly obliged with enforcement action which dragged on for years before a planning inspector, Peter Macdonald, to his credit, issued a ‘who cares?’ decision notice in its favour, rather in the face of the evidence. And now, in accordance with the rules of social normalisation, ‘Untitled 1986’ has been included in the Oxford Heritage Asset Register, to the outrage of the owner, and with its original and still pertinent message lost in the Banksyan bravura. Pasolini would have loved it.

In Pasolini’s words: ‘Oh unfortunate children, you had within reach a wondrous victory that didn’t exist!’. But maybe it does. The world is changing. Perhaps another generation will be more fortunate.

This article originally appeared in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 172, published in June 2022.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

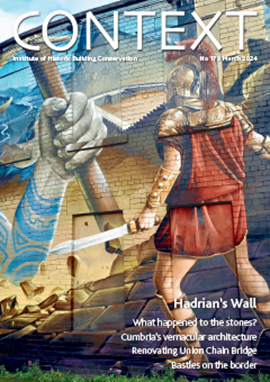

IHBC Membership Journal Context - Latest Issue on 'Hadrian's Wall' Published

The issue includes takes on the wall 'end-to-end' including 'the man who saved it'.

Heritage Building Retrofit Toolkit developed by City of London and Purcell

The toolkit is designed to provide clear and actionable guidance for owners, occupiers and caretakers of historic and listed buildings.

70 countries sign Declaration de Chaillot at Buildings & Climate Global Forum

The declaration is a foundational document enabling progress towards a ‘rapid, fair, and effective transition of the buildings sector’

Bookings open for IHBC Annual School 12-15 June 2024

Theme: Place and Building Care - Finance, Policy and People in Conservation Practice

Rare Sliding Canal Bridge in the UK gets a Major Update

A moveable rail bridge over the Stainforth and Keadby Canal in the Midlands in England has been completely overhauled.

'Restoration and Renewal: Developing the strategic case' Published

The House of Commons Library has published the research briefing, outlining the different options for the Palace of Westminster.

Brum’s Broad Street skyscraper plans approved with unusual rule for residents

A report by a council officer says that the development would provide for a mix of accommodation in a ‘high quality, secure environment...

English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023

Initial findings from the English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023 have been published.

Audit Wales research report: Sustainable development?

A new report from Audit Wales examines how Welsh Councils are supporting repurposing and regeneration of vacant properties and brownfield sites.

New Guidance Launched on ‘Understanding Special Historic Interest in Listing’

Historic England (HE) has published this guidance to help people better understand special historic interest, one of the two main criteria used to decide whether a building can be listed or not.