Conservation officers in historic towns

This article originally appeared in Context 144, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in May 2015. It was written by Richard Bate.

A report for Historic England showed that not all local authorities realise how important conservation officers are to the job of protecting the integrity of historic towns.

There are statutory obligations on local planning authorities to determine applications for planning consent, listed building consent and scheduled monument consent, among others, but no formal requirement to address the heritage interest in whole historic towns and cities. Conservation officers must inevitably prioritise legal requirements, while staff cutbacks limit the chance for engagement in big-picture conservation at the local level. Some of the impacts of this have been identified in a report for English Heritage on The Sustainable Growth of Cathedral Cities and Historic Towns. (Ref Green Balance with David Burton-Pye, The Sustainable Growth of Cathedral Cities and Historic Towns, English Heritage, 2014).

The report focused first on the scale of urban growth within and around a sample of 50 historic towns, where development was both taking place and planned. This showed that there was little relationship between the size of town and the amount of different types of development expected there. Although some historic towns did seem to be overwhelmed, this was not a function of whether or not they were ‘historic’.

Second, the report identified the attention paid to heritage at the whole-town scale in the preparation and implementation of local plans affecting 20 historic towns. In the 18 authorities covering these towns, conservation officers were usually consulted by planning policy colleagues on emerging plan policies. In most cases conservation advice was usually followed by planning policy staff, but in four authorities conservation officers’ views were not taken particularly seriously. Much the same applied to individual development management proposals. In a few cases the conservation officer was the only person in the department who understood heritage issues and was marginalised. Shortage of conservation staff in an authority could result in the conservation officer being insufficiently engaged in the wider planning process, even not being reliably aware how their comments were treated in subsequent decisions.

The research found that councillors generally followed officers’ recommendations on heritage issues, although interviewees suggested occasionally that planning officers did not seem to put forward recommendations to protect heritage buildings if the councillors would be likely to refuse these. Senior staff were unsympathetic to heritage in a few authorities, but the driving force was the attitude of councillors. The economic wellbeing of towns was councillors’ primary concern everywhere, and this was interpreted differently from place to place. Councillors might see heritage either as fostering a town’s distinctiveness, attracting visitors and raising the quality of life (as was the view in Winchester and Woodbridge), or as a cost burden and a drag on investment (the view in Taunton and Wigan).

The observed differences in heritage outcomes were primarily a function of the prevailing local authority cultural attitudes at member level. Broadly speaking, the process reinforced itself, with the relative priority given to heritage by councils reflected in the numbers of conservation staff employed; whether conservation staff were actively engaged in planning major development sites; the amount of proactive work on heritage undertaken; the policies adopted; and the practical decisions taken.

The third strand of the research investigated methodologies which had been used to protect the character and setting of cities at the urban scale, while accommodating growth. This focused on what had been achieved in case studies in eight cities: historic characterisation methods in Lichfield; view cones to protect skylines and the setting of Oxford; height limits and land allocations to protect the setting of Salisbury Cathedral; high-quality design to enable urban intensification in Chester; an urban extension to Winchester; urban intensification outside the historic core in Cambridge; new settlements around Cambridge; urban containment by green belt around Durham; and world heritage site status for the whole city of Bath.

[Image: Urban intensification in Cambridge: the Accordia housing development at 40 dwellings per hectare. (Photo: © Historic England)]

[Image: Mill-style development in Chester: integrating new development into the historic city. (Photo: © Historic England)]

[Image: Salisbury Cathedral from Old Sarum, two miles to the north. The setting of the cathedral has been protected by keeping city centre buildings to below 40ft high and by preventing development on key sites around the edge of the city. (Photo: © Historic England)]

The research found that methodologies alone would not resolve the growth pressures which historic places faced. There were vitally important underlying matters that must be resolved at the same time. There were two essential requirements. One was to foster a favourable climate of support for heritage among local councillors, as previously noted. The other was the need for a properly resourced conservation and design service in local government. Only if there were enough professionals to pursue the objectives would there be any hope of achieving good results. Cutbacks in local government have often affected local heritage interests badly and this needs to be tackled as a priority.

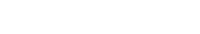

Conservation officer numbers in the eight case study cities were examined. The table shows how few conservation staff were employed even in some of England’s most important historic cities. There have been cutbacks everywhere, particularly severe in Chester at the time of the survey. Interviewees expressed concern in some cases that the loss of even one member of staff had substantially curtailed conservation officer capacity to engage with city-scale heritage issues.

Heritage was represented well enough at senior officer level in most authorities, but there were two cities where supportive structures had been lost in internal reorganisations, so that heritage was now a minor activity in a structural backwater. Conservation officers’ access to councillors also varied.

Local government reorganisation, with the establishment of larger, unitary authorities, had been a particular trigger for reduced conservation staff serving Chester, Durham and Salisbury. In each case the local priority given to protecting these heritage cities was diluted. Cooperative working between local authorities suggests that local government reorganisation may not be over, so conservation bodies need to be more alert in future to establishing reliable operating standards in new authorities.

Some of the cities were nonetheless offering broadly positive messages for conservation. A principal message from growing cities like Cambridge, for example, was to take a very positive attitude to development, expecting it to happen and making it good. High expectations for all aspects of design, clear policies and extensive pre-application discussions with developers helped to achieve good development, but these needed to be supported by staff with the design skills to recognise and require the necessary standards. This means that the process must be properly resourced. Heritage buildings and their surroundings should be planned-in to developments from the outset, not treated as a problem.

There has been a remarkable loss of perspective in some authorities. All the historic cities studied now depend on a significant tourist industry, in some cases underpinning the local economy. This brings in prodigious wealth in some cases, all the more important when the local authority is itself a significant local landowner. This wealth is generated fundamentally by the physical environment and especially the built heritage. The maintenance of this built heritage and the avoidance of direct damage to it or inappropriate change to its context is the task of a tiny group of individual conservation officers in each city, yet their numbers and sometimes their status and ability to do their job are sometimes being undermined. Over time this will put at risk the fabric and especially the atmosphere and enjoyment of historic cities.

The paltry savings on modest salaries seems wholly misplaced in relation to the potential benefits of retaining and augmenting conservation staff. The costs would be barely detectable in relation to the wealth that the historic environment brings to these cities. This is a matter to little thought has been given in historic cities, even in those which realise that heritage is good for the economy. Partly behind this may be an undercurrent of feeling, detectable in many administrations, that historic buildings and their surroundings are simply ‘there’ and look after themselves. Changes on the ground do not register strongly from one year to the next, but over time they do. By then it may be too late, with inappropriate uses allowed in the wrong place, vistas compromised and shoddy materials used, and people with the drive to stem the tide strangely absent.

The report recommends that local authorities responsible for the management of England’s important historic places should ensure that they have access to adequate expert advice in historic environment (building conservation and archaeology), design and place-making. Having sufficient expert advice is the most important practical step that can be taken to reconcile the protection of heritage at the whole-town scale with the needs for urban growth. There is little prospect of other bold initiatives being successful without this recommendation being satisfied first.

Richard Bate is a partner in the planning and environment consultancy Green Balance.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Archaeology.

- Conservation officer.

- Conservation practice survey 2016.

- English Heritage.

- IHBC articles.

- Impact of heritage sector local authority funding cuts in south west England.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Listed building.

- Local authority conservation specialists jobs market 2014.

- Loss of senior conservation staff and posts in England March 2010 to April 2011.

- Planning authority duty to provide specialist conservation advice.

- Scheduled Monument Consent.

- World Heritage Site.

IHBC NewsBlog

Heritage Building Retrofit Toolkit developed by City of London and Purcell

The toolkit is designed to provide clear and actionable guidance for owners, occupiers and caretakers of historic and listed buildings.

70 countries sign Declaration de Chaillot at Buildings & Climate Global Forum

The declaration is a foundational document enabling progress towards a ‘rapid, fair, and effective transition of the buildings sector’

Bookings open for IHBC Annual School 12-15 June 2024

Theme: Place and Building Care - Finance, Policy and People in Conservation Practice

Rare Sliding Canal Bridge in the UK gets a Major Update

A moveable rail bridge over the Stainforth and Keadby Canal in the Midlands in England has been completely overhauled.

'Restoration and Renewal: Developing the strategic case' Published

The House of Commons Library has published the research briefing, outlining the different options for the Palace of Westminster.

Brum’s Broad Street skyscraper plans approved with unusual rule for residents

A report by a council officer says that the development would provide for a mix of accommodation in a ‘high quality, secure environment...

English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023

Initial findings from the English Housing Survey 2022 to 2023 have been published.

Audit Wales research report: Sustainable development?

A new report from Audit Wales examines how Welsh Councils are supporting repurposing and regeneration of vacant properties and brownfield sites.

New Guidance Launched on ‘Understanding Special Historic Interest in Listing’

Historic England (HE) has published this guidance to help people better understand special historic interest, one of the two main criteria used to decide whether a building can be listed or not.

"Conservation Professional Practice Principles" to be updated by IHBC, HTVF, CV

IHBC, HTVF, and CV look to renew this cross-sector statement on practice principles for specialists working in built and historic environment conservation roles.